By Justin Parkoff, MA

Project Manager / Conservator

Conservation Research Laboratory

Texas A&M University

This past Fourth of July, I went to Port O’Connor to watch the fireworks over Matagorda Bay. Thousands of people watched in awe along the shoreline, while hundreds of little fishing boats dotted the water. The display was loud and magnificent, contrary to the normally quiet life in Port O’Connor, or for any of the sleepy little towns that lie along the bay. As I sat there watching the celebration I found it hard to imagine that over a hundred and fifty years ago, a massive blockade of warships lined the coast of Texas and Union gunboats raided these towns. From where I was sitting, I would have been able to watch USS Westfield and USS Clifton steam by on their way to capture Indianola and bombard the town of Lavaca. This realization was very special to me, since for last five years I have been leading the efforts at Texas A&M University to conserve and restore thousands of artifacts that were recovered from the wreckage of Westfield.

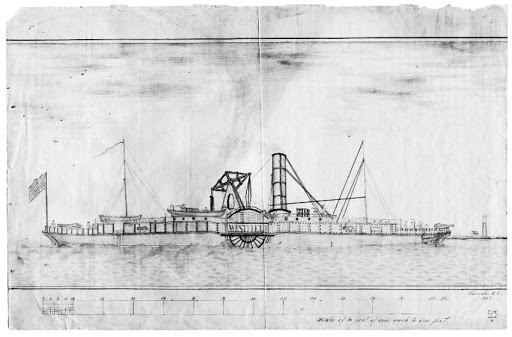

When the Civil War broke out, the Union navy realized that they were ill prepared to fight naval battles in their own backyard. The warships in service were heavy and deep drafted vessels that would not be able to navigate the shallow bays and twisting rivers of the southern states. This led the navy to purchase thousands of shallow drafted vessels, including Westfield, which were converted into warships. Westfield was originally a New York Staten Island ferryboat, built for and owned by the famous Cornelius Vanderbilt. As a ferryboat, the vessel contained an identical bow and stern so that the vessel could travel in either direction. This feature allowed Westfield to travel into very confined spaces without the need to turn around. Additionally, Westfield was built to carry extremely heavy loads of passengers and horse teams, a design aspect that was utilized by the navy for carrying heavy artillery and other armaments.

After aiding Admiral Farragut in the successful capture of New Orleans, Westfield was sent to Texas to serve as the flagship for the West Gulf Blockading Squadron. Her mission was to maintain the blockade, and to isolate or capture major port towns. As the largest port in Texas, Westfield first captured Galveston on October 9th, 1862, and used the city as a base of operations to conduct raids up and down the Texas coast. The Union held this city until the Battle of Galveston, on January 1, 1863. In the early hours of New Year’s Day, Confederate forces under the command of General John B. Magruder launched a joint land and naval attack on the city. During this battle, Westfield ran hard aground while trying to cut off enemy vessels. Facing capture, Westfield’s commander, William B. Renshaw, made the difficult choice to destroy the vessel rather than let her fall into enemy hands. Renshaw ordered that turpentine be poured upon the decks, the safety valves on the boilers be shut, and that the forward gunpowder magazine be opened. After lighting the fuse, the resulting explosion blew off Westfield’s bow, destroying the vessel, and accidently killed Renshaw and twelve of his men. For ten minutes the stern of Westfield sat smoking as the trapped steam from the boilers rose into a loud audible scream. Then, there was a second blinding flash when the boilers ruptured. The remains of Westfield burned to the waterline and slipped beneath Galveston Bay. By the end of the battle, Galveston lay in Confederate hands, and the remaining Union ships fled the bay.

In 2009, Westfield’s wreck site was relocated in advance of a major dredging operation planned by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The remains of the vessel consisted of a disarticulated debris field. To prevent the destruction of these remnants, the USACE orchestrated the largest archaeological salvage project that has ever been conducted in Texas waters. Over 8,000 artifacts were successfully recovered, including a 9 inch smoothbore Dahlgren cannon. These artifacts were ultimately sent to Texas A&M University for analysis and conservation.

Following conservation, a new problem arose in how to present these artifacts to the public. While many of the smaller artifacts from the crew were unique and educational, the majority consisted of shattered machinery and boiler parts. Very little survived that could be easily developed into an interpretive museum exhibit. Individually, these shattered artifacts meant nothing. However, if these artifacts could be combined and somehow exhibited together as a whole, the image of Westfield and her story might come to light. As conservators at Texas A&M University, our goal shifted. Rather than displaying individual artifacts from the ship, we are instead utilizing all of the artifacts together and rebuilding massive sections of the vessel’s machinery. These surviving artifacts will appear in the Texas City Museum on a skeletal structure that will demonstrate the original size of the machinery. Secured to the skeletal frame, hundreds of twisted artifacts will help museum patrons experience the devastating nature of Westfield’s explosion.

Raising funds for this exhibit has been a challenge. Along with support from the Texas City Museum, outside funding from groups like the Fort Worth Civil War Round Table have enabled this project move past this challenge and bring Westfield’s story to light. Thank you for your time, financial contributions, and believing in this project. As the project progresses, the Conservation Research Laboratory will keep your organization updated, so that you might enjoy visiting during the grand opening of the exhibit, or in the years to follow.